Part 2 of our Product Operating Model Transformation Series

Six weeks into our product operating model transformation, I sat in a conference room watching our VP of Product present a beautifully crafted deck to the executive team. Slide after slide showcased our “progress”—new frameworks implemented, discovery sessions conducted, outcome metrics defined. The executives nodded approvingly. The presentation was polished, professional, and completely divorced from reality.

Meanwhile, down in the trenches, our product teams were drowning. They were trying to balance their existing feature factory commitments with new discovery work, attending twice as many meetings, and producing deliverables for both the old system and the new one. Our engineering teams were frustrated by the constant context switching. Our designers were burning out from being pulled in multiple directions.

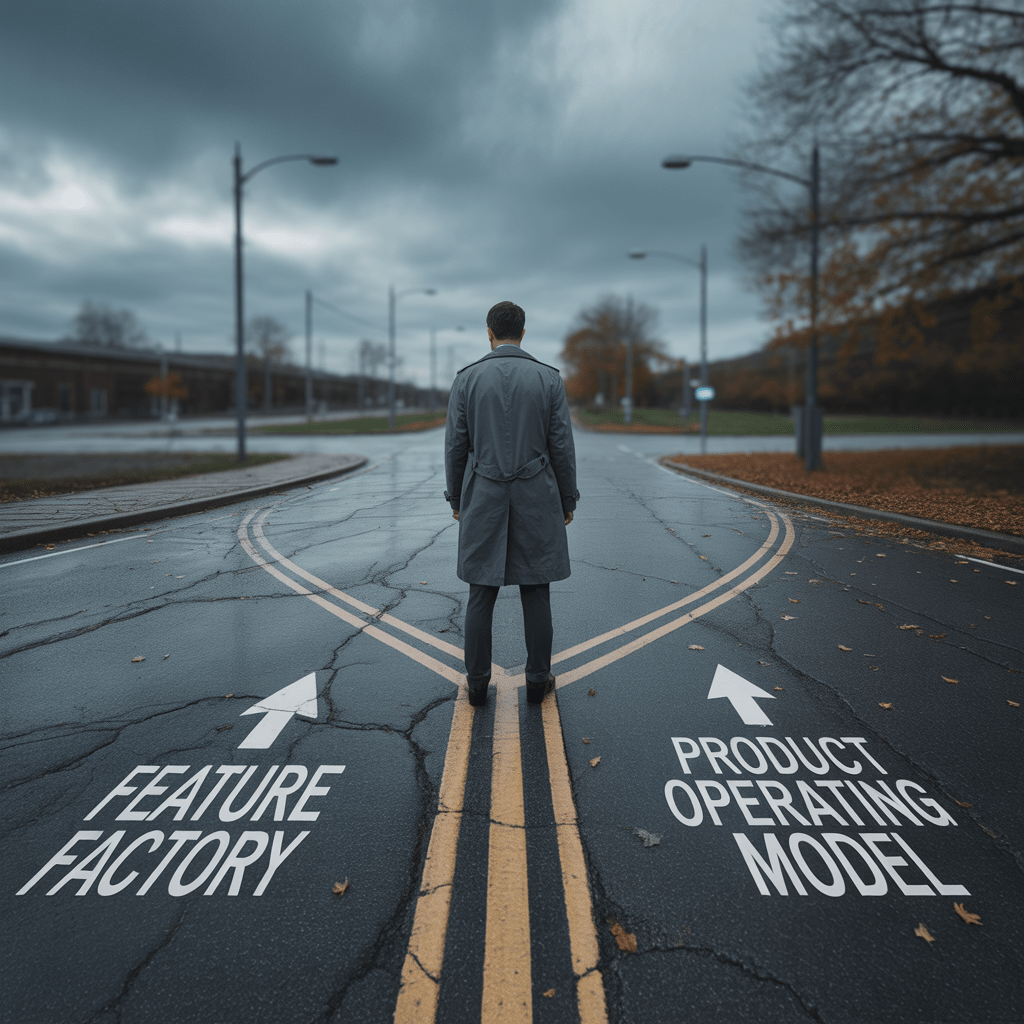

We had fallen into the biggest trap that dooms transformation efforts: trying to run two operating models simultaneously.

The “Both/And” Delusion

Here’s the mistake almost every company makes when attempting to transform: they try to keep the old way of working while layering the new way on top. They want to maintain their current velocity while also implementing discovery practices. They want to keep hitting feature delivery deadlines while also focusing on outcomes. They want to preserve existing stakeholder commitments while empowering teams to make decisions.

It’s like trying to drive a car while also riding a bicycle at the same time. You’re not going to excel at either—you’re just going to crash.

In our case, leadership was terrified of losing momentum. “We can’t just stop delivering features while we figure this out,” our VP argued. “The business won’t stand for it.” So we tried to do both. Product managers were expected to continue their roadmap commitments while also conducting user interviews and running experiments. Engineering teams had to deliver predetermined features while also building hypothesis-driven prototypes.

The result? Nobody was doing either thing well.

Why “Both/And” Always Fails

Let me be clear about why this approach is doomed from the start:

Different Operating Models Require Different Rhythms

Feature factories operate on prediction and delivery cycles. Product operating models work on discovery and validation cycles. These rhythms are fundamentally incompatible. You can’t plan features six months out while also being responsive to customer discovery insights.

Competing Success Metrics Create Confusion

When you’re measuring teams on feature delivery velocity AND customer outcome improvements, you’re essentially asking them to optimize for contradictory goals. Teams end up gaming whichever metric feels safer (spoiler: it’s usually the delivery metrics).

Resource Allocation Becomes Impossible

Discovery work requires dedicated time and mental space. You can’t squeeze meaningful customer research into the gaps between feature delivery sprints. Something has to give, and it’s usually the discovery work because delivery deadlines feel more urgent.

Teams Lose Trust in Leadership Commitment

When teams see that leadership won’t make hard choices about priorities, they quickly realize the transformation isn’t actually important. They start treating the new practices as compliance theater while focusing on what they know really matters—hitting delivery targets.

The Real Cost of This Mistake

Our dual-operating-model approach lasted about four months before it completely collapsed. Here’s what we lost in the process:

Team Morale: People were exhausted and cynical. They felt like leadership was asking them to do twice the work without any additional resources or support.

Stakeholder Confidence: Business stakeholders started questioning the value of the transformation when they saw teams struggling to deliver on existing commitments.

Credibility: When we finally had to choose between the old way and the new way, many people had already checked out. They’d seen too many “strategic initiatives” layered on top of their existing work.

Time: Those four months of trying to do everything meant we were four months behind where we could have been if we’d made clean choices from the start.

What We Should Have Done Instead

Looking back, here’s what a successful approach would have looked like:

Make the Binary Choice

Leadership needed to decide: are we a feature factory or are we adopting the product operating model? There’s no middle ground. Pick one and commit to it fully.

Create Protected Space

If you’re transitioning to the product operating model, you need to create actual space for teams to learn and practice new ways of working. This means reducing or pausing some existing commitments, not adding new ones on top.

Communicate the Trade-offs Clearly

Be honest with stakeholders about what you’re not going to do while you transform. Yes, feature delivery might slow down temporarily. Yes, some roadmap commitments might need to shift. That’s the price of transformation.

Start with Pilot Teams

Instead of trying to transform the entire organization at once, select pilot teams that can operate purely in the new model while other teams continue with existing approaches. This gives you proof points and learning opportunities without the chaos of organization-wide change.

The Hardest Part: Leadership Courage

The real reason companies fall into the “both/and” trap isn’t because they don’t understand the trade-offs. It’s because making binary choices requires courage from leadership.

It takes courage to tell stakeholders that some features will be delayed while teams learn new ways of working. It takes courage to defend teams when they’re moving slower during the transition period. It takes courage to stick with the transformation when early results are mixed.

Our leadership team lacked that courage. They wanted the benefits of transformation without the short-term costs. They wanted to appear decisive without making difficult decisions. They wanted transformation to be additive rather than substitutional.

The Warning Signs You’re Making This Mistake

Watch out for these red flags in your own transformation:

- Teams are being asked to maintain existing delivery commitments while adopting new practices

- Success metrics include both delivery velocity and outcome improvements without clear prioritization

- Discovery work is happening “when teams have time” rather than being scheduled as primary work

- Stakeholders are complaining that transformation is slowing down feature delivery

- Teams are treating new practices as compliance exercises rather than genuine ways of working

How to Course-Correct

If you recognize these patterns in your organization, here’s how to get back on track:

Stop the Madness

Have an honest conversation with leadership about the impossibility of running two operating models simultaneously. Present the data on team burnout, delivery struggles, and transformation progress (or lack thereof).

Force the Choice

Make leadership pick: transformation or status quo. If they choose transformation, that means some existing commitments have to change. Get specific about what will be paused, delayed, or cancelled.

Protect the New Way

Create space for teams to actually practice the product operating model without the burden of also maintaining the old way. This might mean dedicated transformation time, reduced delivery expectations, or pilot team structures.

Measure What Matters

Align your metrics with your chosen approach. If you’re transforming to the product operating model, start measuring customer outcomes and discovery activities. Stop rewarding delivery velocity during the transition period.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here’s what nobody wants to admit: transformation requires sacrifice. You can’t get the benefits of the product operating model without giving up some aspects of how you currently work. You can’t empower teams without reducing centralized control. You can’t focus on outcomes without sometimes missing output targets.

The companies that succeed at transformation are the ones willing to make these trade-offs explicitly and defend them consistently. The companies that fail are the ones that try to avoid making hard choices.

What’s Next

In our next post, we’ll dive into how to select your pilot team to trial the change—because once you’ve made the choice to transform, you need to be strategic about where you start. We’ll explore the characteristics that make some teams better candidates for transformation than others, and how to set them up for success.

Until then, take a hard look at your current transformation efforts. Are you trying to run two operating models at once? If so, it’s time to make some difficult but necessary choices.

This is part 2 of our Product Operating Model Transformation Series. Coming up next: “How to Select Your Pilot Team to Trial the Change”

Have you seen organizations try to run dual operating models? How did it work out? Share your experiences in the comments below.

Leave a comment